|

The

Inspiration of MID-LIFT®

Rocker Arms

This is from where all MID-LIFT®

geometry evolved since it was developed

...more than 43 years ago!

|

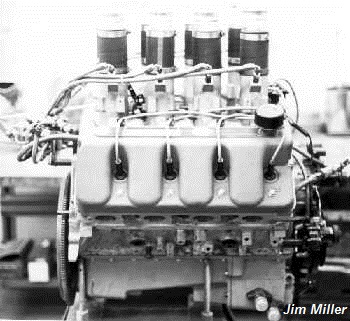

(CLICK PHOTO FOR MODIFIED

1980 BOSS MANIFOLD)

|

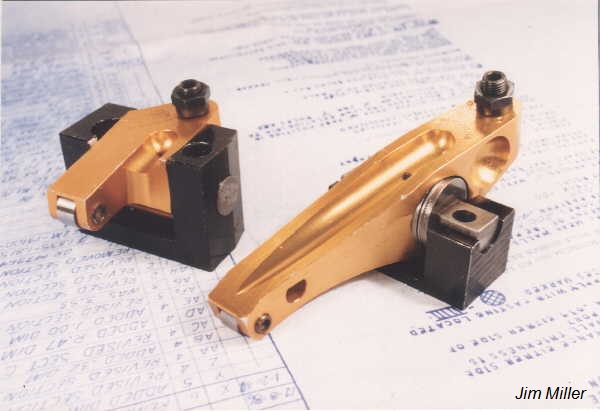

(FOR BOSS ROCKERS CLICK PHOTO) |

|

Ford's

BOSS 429 crossed over

into CAN AM racing, displacing 494 cubic inches. It's torque was phenomenal,

prompting quite a few of these FIRST aluminum block Ford BOSS engines to be

used in pursuit boats, sold to Arab nations; similar to Scarab (Miami Vice)

style boats, with two and three engines each. Ford's independent Grand

National contractor, Holman-Moody, was behind all these famous variations,

and many other of Ford's exotic racing endeavors. |

Miller

BOSS 429 Series III Rockers

(1983). Jim Miller was the FIRST designer who

understood the detriment of side thrust harmonics and their loads upon compound

geometry valve trains. Jim has used Torrington Thrust bearings since 1983,

and implemented them on all

PRO-SHAFT NASCAR designs whenever any side load

inclines from the push-rods was evident on the head's X-axis. But it was on

the extreme angled BOSS 429 where they were developed and used first. |

The Roots of MID-LIFT

originates from the most complex valve train of any American racing engine!

(Everything since has been easy.)

BOSS 429 Ford

"BLUE CRESCENT"

Designed in 1968, implemented in 1969, the

BOSS 429

was Ford Motor Company's answer to their failed attempt to introduce the

Over-Head Cam 427 Side Oiler into NASCAR's Grand National racing, and regain

their competitive edge against Chrysler's dominant 426 Hemi. Ford took their

"attitude" for overkill engineering originally directed into the 427 SOHC, and

took NASCAR's no over-head-cam rule to the recently new block

originally designed for the truck and big car market, known as the

"385 Series," for its 3.85" stroke crank; but it was more familiar as the

"460." It was soon de-stroked to a 3.59" crank and adapted as the 429 wedge,

429CJ, and 429SCJ. All these basic variations followed a common cast iron

cylinder head canted valve array, including a few quirk aluminum head castings

based on the SCJ. They were very similar to the Chevy 427 combustion chamber, except

all intake ports were parallel designs (not symmetrical - left and right

variations, as the BB Chevy). The BOSS 429 "head" was adapted to this engine

block, but only after some oil galley and deck transfer holes were engineered to

be precision machine for the novel individual gasket rings. The BOSS 429 sported many conceptual ideas of airflow from the 427 SOHC,

and 427 TUNNEL PORT, mainly round intake ports, but HUGE (for their time); a

hemispherical combustion chamber, that was "clipped" on each side just a tad,

creating a design that was coined "semi-hemi" and "crescent" -- and later became

known as the BLUE CRESCENT Hemi. Where Ford really got complex, was their

initiative to introduce a flow technology that had been briefly tested on more

exotic engine designs, but never an American OHV engine. It was later coined as "swirl"

technology. One of the concepts to swirl technology is to purposely place the

valve angles and their related port windows feeding them (as well as the port

shape) in such a manner that a preset direction of flow is used to do more than

just fill the chamber. It induces a cross-flow over the piston and to move

across to the

exhaust valve which sets up a circular pattern of chamber burn and purging. The

aim is more efficient flame propagation, which wedge chambers are good at, but

lack in the cross-flow efficiency to purge as well as a hemi. To accomplish

this the BOSS 429 had its opposing intake and exhaust valve axis rotated 26°

from perpendicularity to the piston's wrist pins. This required considerable creative thinking

for passing the pushrods through the heads for complex mounting angles of the rocker arms. Unlike the 427

Tunnel-Port, where they simply went straight through the port with surrounding

sleeves to isolate the two systems, the valve train was laid over on compound

angles, which became the most complex rocker geometry of

any American made Overhead Valve (OHV) engine; even to this day, nearly 50

years later.

--jM

(Revised, 2016)

^

The concept of MID-LIFT® geometry began

back in 1973, and by 1974 it was finalized into the principles of

precision geometry that Jim Miller developed for the Ford's BOSS 429

Grand National NASCAR engine. You don't have to be a

"Ford fan" to appreciate that in 1968, when this engine was first taken from the

drawing boards of Ford's racing division to a real engine for racing in 1969, it

had set a precedent for airflow, volumetric efficiency, horsepower per cubic

inch, and sheer, all out "WOW" factor, that no other engine of that era had

done. But it was flawed in a couple of small respects.

One, was its valve train. COMPLEX.

Meaning: it was a semi-hemispherical combustion chamber, with quenched side

walls to contain the cross flow intentions of a hemi chamber, but the intake to

exhaust valve's opposing angles were "twisted" on a 26 degree rotation to the

piston's wrist pin. The rocker arms were independently mounted on pedestals cast

and machined at precise compound angles. But like another engine Ford made the

same mistake with, the attachment to the block for pushrod angles was required

to work with lifters that were "in-line" rather than laid over for dedicated

exhaust and intake rocker locations. Plus, the pushrod's side angle array was

heavily leaned away from the tappet centerlines too.

^

|

|

|

Factory INTAKE |

Factory EXHAUST |

The cylinder head's huge round

ports and location, required this twisting of the valve to valve centerlines,

but Ford was also chasing induced swirl technology, very new for OHV engines of

that period. But to make all the parts fit between where the pushrods would exit

through the heads, and the valve tips needed to be, meant that the rocker arm

dimensions would be extreme in both directions. The INTAKE rocker was one of the

shortest designs used on any American engine, rivaling the small block

Chevrolet. The EXHAUST rocker was the longest, exceeding the Chrysler

hemi. The pushrods themselves were also among the longest in use, with the

exhaust reaching nearly 11" in length.

^

In 1972, for "Grand National"

racing (as Winston Cup style NASCAR was known in those days), the typical 7,800

rpm hemi engines with barely .650" valve lift could accept these crazy

valve-train arrays. But drag racing's high rpm, quick shock to the drive train

was entirely different. For Jim Miller's de-stroked 409ci B/MP BOSS Mustang,

that launched from the line at 9,000 and hit the 1/4 mile traps at 9,300 rpm; no such

designs were possible, without breaking something on each pass. This was the beginning of

questions for an engine few people understood, compared to the masses of

information accrued over the years for Chevrolet and Chrysler engine builders.

Rocker arm questions, for instance. To begin designing his own rockers, Jim

needed a foundation from how other designs were done. But even

questions asked with the common Chevrolet engines, Jim Miller soon learned there

was no comparable dimensions for various manufacturers on their rocker arms.

Center-to-center lengths for the critical stud to valve, as well as the arcing

motion across the valve, were all undecided specifics between individual

manufacturers. Rocker arm "height" on the stud (or shaft, as in the Ford 390-428

FE engine) was also a question that no cam manufacturer selling rocker arms

would answer, beyond "keep the rocker on the tip of the valve."

^

MILLER MID-LIFT™

The Standard By Which All Is Measured!™

954-978-2171 MillerRockers@aol.com

MID-LIFT™, PRO-SHAFT™ & PRO-STUD™ are JM Miller Trademarks; Copyright © MMIII~MMXXIV

| |